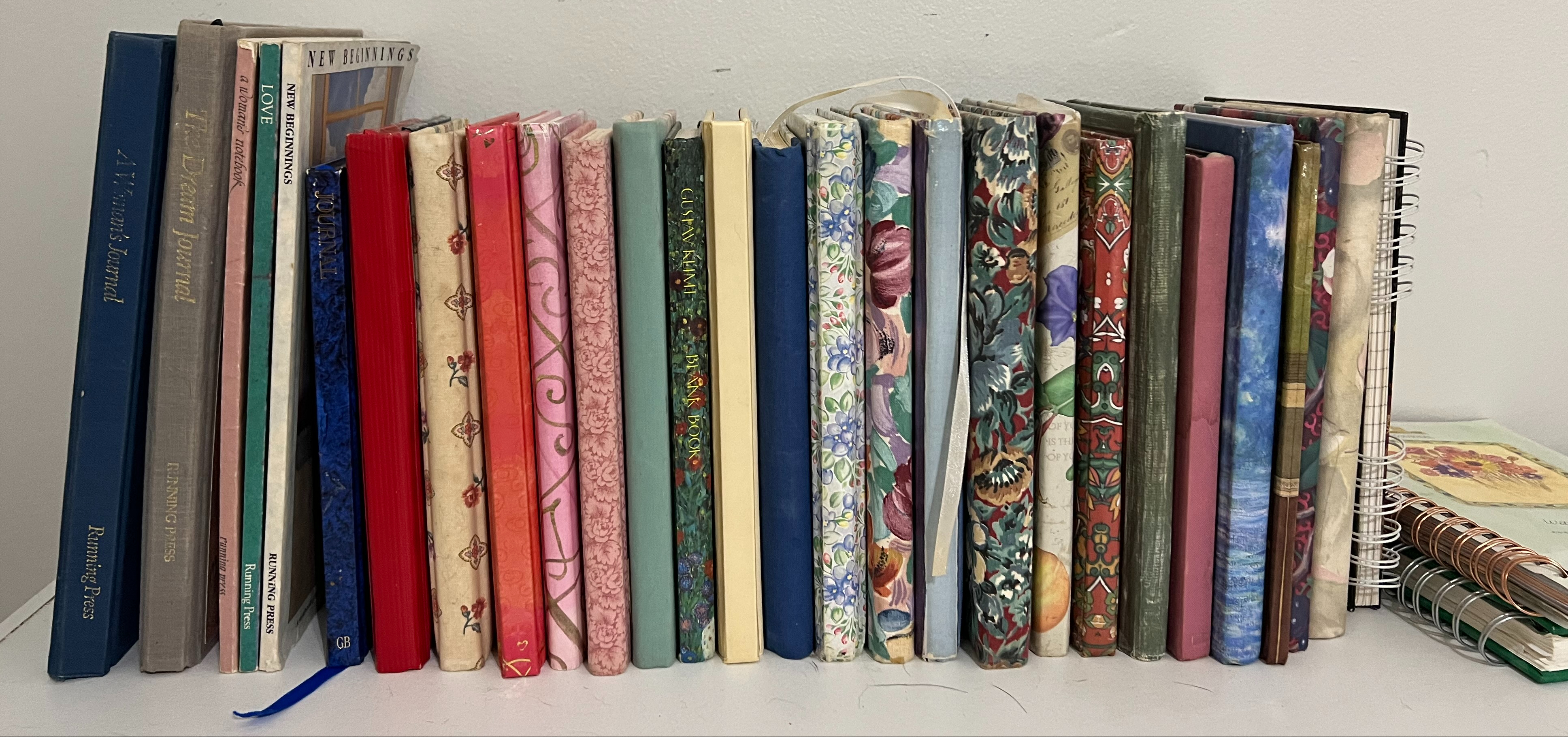

Today, June 21, 2022, I celebrate 20 years of sobriety. I’m grateful. And deeply reflective. In recovery, we’re not supposed to “regret the past, nor shut the door on it.” It seems I had done a bit of both. I recently dug out a box of old journals. Very quickly, memories flooded back.

6/8/02 I’m slowly killing myself and must stop. I know I need help. How do I get it? How do I face everyone? How do I conquer the demons inside? The demons that dominate. By the grace of God, I still have hope for a brighter tomorrow.

That gift of hope kept me going a long time. But on June 20, 2002, I got something greater: the gift of desperation. My husband couldn’t take my drinking anymore. I realized then: I couldn’t either. I needed—and finally wanted—help. Desperately.

6/21/02 It’s the first day of summer and my first day of sobriety. Here I am, just outside of Nashville, getting treatment for my alcohol “issues.” I feel lonely and uncomfortable. But I’m glad I came.

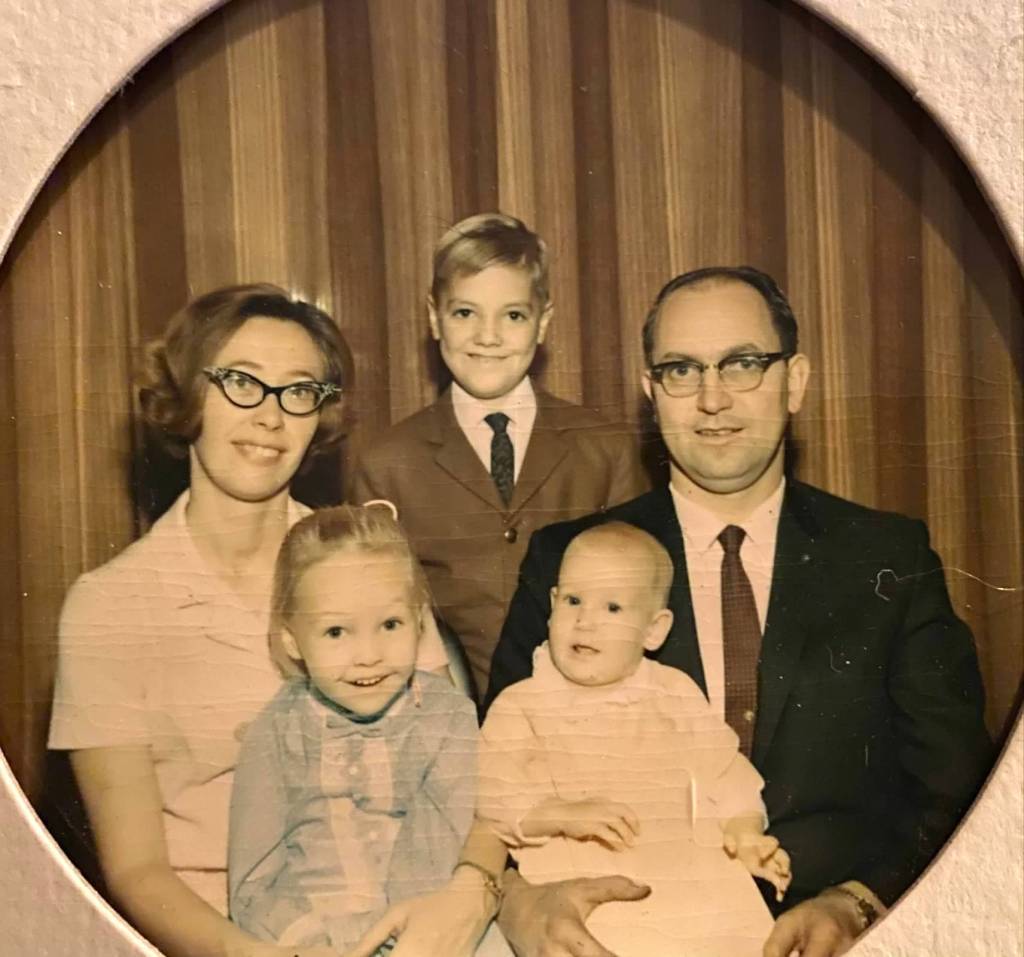

When I started journaling in college, I had no idea I’d begun documenting what would become a 15-year battle with a chronic and progressive disease, along with disordered eating that preceded, and later co-occurred, with my substance use disorder (SUD); the detrimental effects my dad’s drinking had on me; and other co-occurring conditions that further hindered my well-being.

9/23/89 Nice writing last night. Nice state of mind. I can’t believe I got so drunk…. I was so sad the past two days… I have no feelings left. I’ve exhausted my tears.

10/27/95 Why can’t I just be happy with the woman I am? Why the shame? Why the loathing? There’s poison inside of me and it’s killing my spirit.

9/29/97 Alcohol interferes with my health, my love, my marriage and self-respect. Patty Loveless concert was great. But I drank until my mind was mush.

12/21/98 What a stupid, drunken weekend. I feel so low. So unhealthy. So poisoned.

Opening the door to my past has been liberating. I’m recognizing, feeling and, I hope, releasing the pain I internalized many years ago. To fully appreciate where I am, I had to remember where I was. These journals helped me recognize today’s milestone for the miracle that it is.

4/28/02 Mom knows I’m an alcoholic. It’s in her voice. I know it too. It’s an agonizing reality. I’m imprisoned by it. I wish I could be normal. No crazy obsessions. No horrible habits. Just normal. How hard could that be?

Very hard if you suffer from addiction or other mental health-related conditions. While incurable, SUDs and mental illnesses are treatable. It’s not a habit to break; it’s an illness to treat. And treatment changed my life.

8/2/02 I relish these Friday nights. Before, I spent them drinking. Too side-tracked to read. Too sloshy to write. We went to Rosie’s. David had two beers. I looked longingly at people around me enjoying their icy, fruity drinks. But I feel remarkably clear and sound.

I rode many pink clouds that year, but life still knocked me off my feet. I lost my dad, just months after I broached the 12-step subject with him.

7/14/02 I asked Dad if he’d ever been to a meeting. “Some time ago.” “Will you go with me sometime?” “We’ll see,” he said, before quickly handing the phone over to Mom.

My wonderful father, who never found relief from his addiction, passed away October 9, 2002. It was strange, grieving without alcohol. Imagine how you feel after working out for the first time in years. You’re sore, but it’s a good sore. When my dad died, that’s how I felt, like I was exercising my emotional muscles for the first time in ages. It hurt, but it was a good hurt. The pain told me: You’re alive. You’re getting stronger.

10/26/02 If I were still drinking, I’d be “sipping” white wine. That socially acceptable beverage would be dulling my pain. That would be an insult to his memory. I wish he had found peace before he died. God’s given him peace now.

People in my recovery circles helped me through that tough time, and others. Just shy of my one-year sobriety date, I lost my job. After I was “let go,” I didn’t go to the liquor store. I went to a meeting.

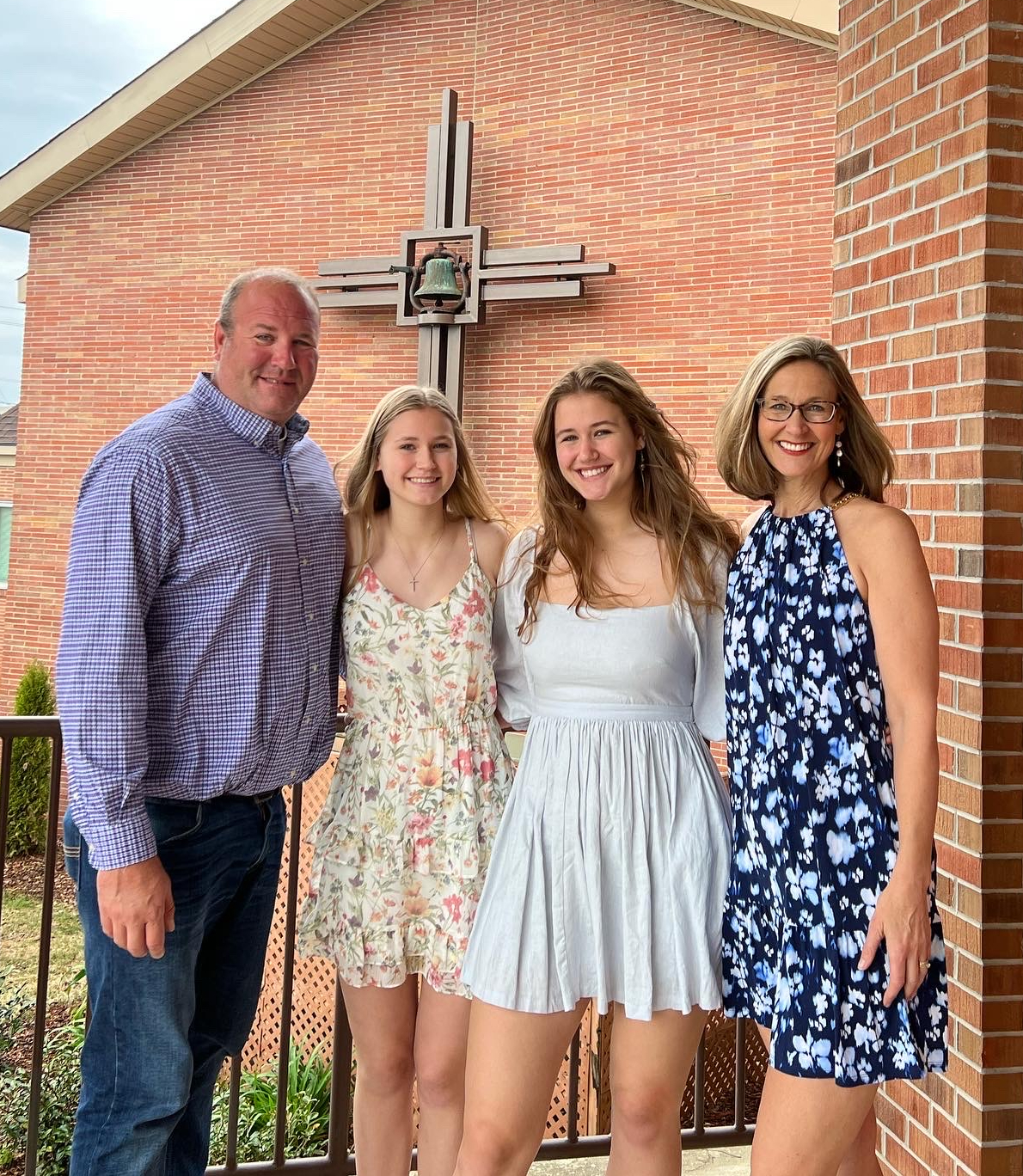

That was a miracle. Other miracles: My husband, David, and I recently celebrated our 26-year anniversary and we have two amazing teenage daughters. Additionally, God led me toward a meaningful career in nonprofit fundraising. I currently work for a mental health center and serve on the board of an addiction resource organization. Last fall, I started sharing my experiences publicly. God gave me renewed purpose, personally and professionally.

Early on, I remember watching “Susan” get her five-year medallion. She said she did it “one day at a time,” adding, “I was a mess. If I can do it, anyone can do it.” I latched onto her words. In vulnerable moments, I’d tell myself, “If Susan can do it, I can do it.”

And here I am, at 20 years. Like Susan, I was a mess (I have the journal entries to prove it). Like Susan, I did it one day at a time. And like Susan, I believe that if I can do it, you can do it. But there’s a catch: You have to want it. If you’re not there yet, consider praying for desperation. It remains one of the greatest gifts I ever received.

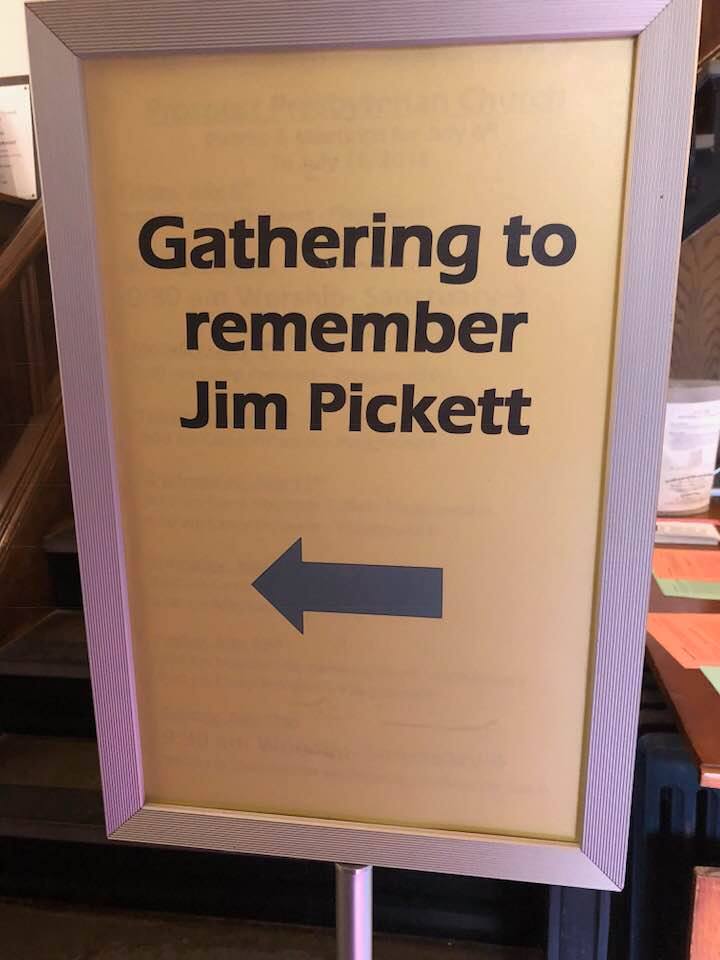

quickly-assembled “Gathering of Remembrance” in Maplewood earlier this month. A standing-room only crowd shared memories from across Jim’s lifetime, depicting a man both well loved and well lived. They highlighted entrepreneurial struggles and triumphs, his remarkable curve ball, and again, his devout loyalty for his friends and unequivocal adoration for his family.

quickly-assembled “Gathering of Remembrance” in Maplewood earlier this month. A standing-room only crowd shared memories from across Jim’s lifetime, depicting a man both well loved and well lived. They highlighted entrepreneurial struggles and triumphs, his remarkable curve ball, and again, his devout loyalty for his friends and unequivocal adoration for his family.

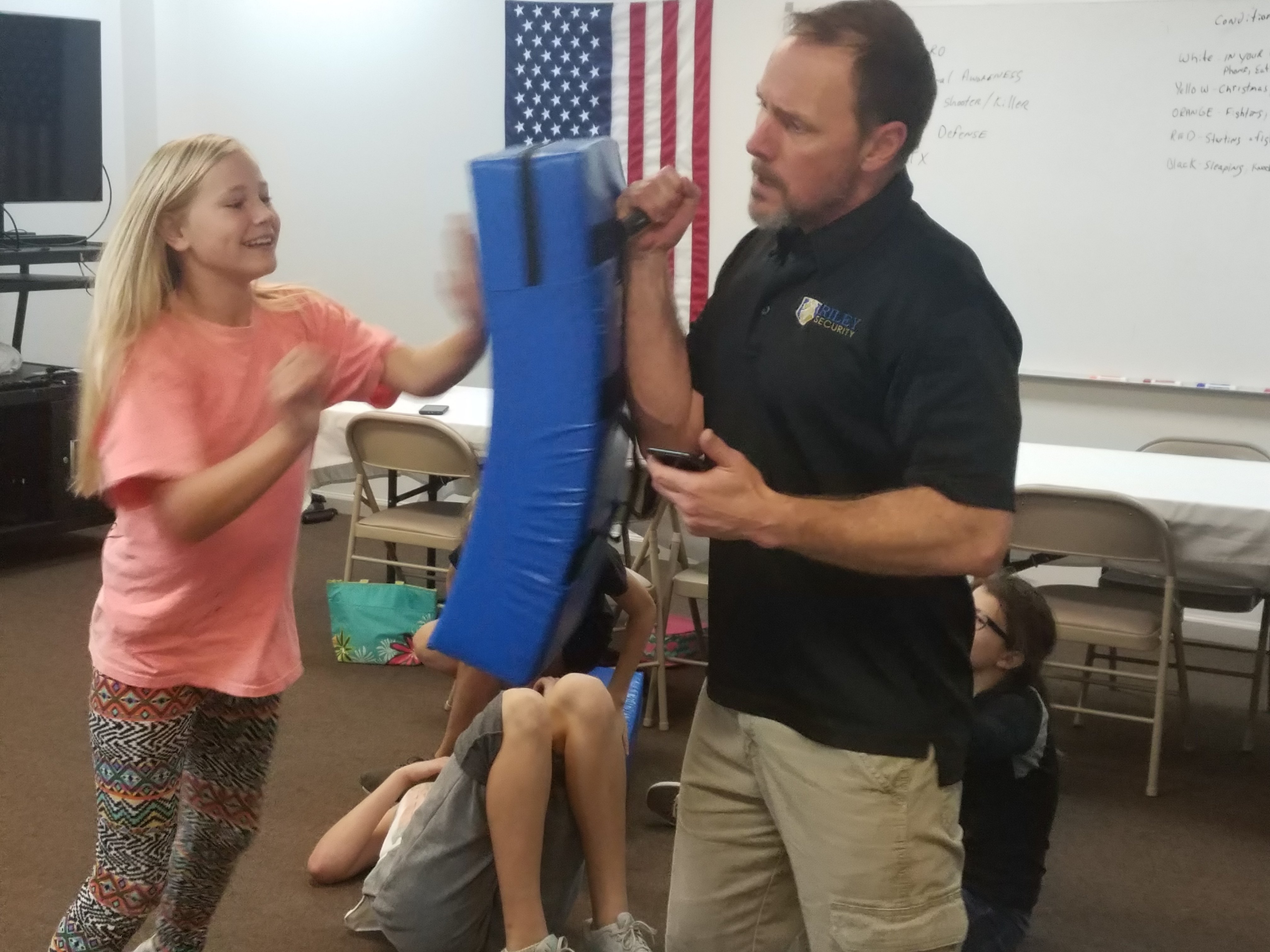

(the face is a key target). Keep hitting, one hand after the other, making sure you keep your non-hitting hand near your face to protect you.

(the face is a key target). Keep hitting, one hand after the other, making sure you keep your non-hitting hand near your face to protect you.